Who are Indigenous People in Canada?

|

Current News Stories |

Received from https://www.itk.ca/about-inuit/inuit-regions-canada

Spotlight: Decolonizing Education

|

In Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit, Battiste (2013) shares her learning journey, critical perspectives, research and activism. Her research largely focuses on the Canadian government, policies resulting in inequity, and complex processes of decolonizing education. A process she describes as belonging to everyone.

Battiste supports meaningful inclusion of Indigenous humanities and sciences. She explains how indigenous knowledge is linked to a specific worldview, connected to place, global sustainability and resource usage. She highlights the importance of redefining our relationship with ourselves, each other and the environment. |

Mi'Kmaq is a noun referring to the Lnu people. Mi'Kmaw is the adjective.

|

Resources to Nourish Your Learning Spirit

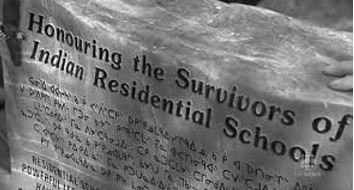

Project of the Heart: It is an inquiry-based, hands-on, collaborative, inter-generational, artistic journey of seeking truth about the history of Aboriginal people in Canada.

Kairos Blanket Exercise: A teaching tool to share the historic and contemporary relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada

Legacy of Hope Foundation: It is a national,Indigenous-led, charitable organization to expand awareness and create just and equal relationships of reconciliation and healing for all Canadians. Bilingual resources are available for educators, students and researchers.

Kairos Blanket Exercise: A teaching tool to share the historic and contemporary relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada

Legacy of Hope Foundation: It is a national,Indigenous-led, charitable organization to expand awareness and create just and equal relationships of reconciliation and healing for all Canadians. Bilingual resources are available for educators, students and researchers.

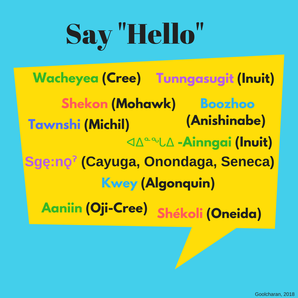

Indigenous Languages

|

There are many Indigenous languages. Do you know which Indigenous languages are spoken in your province? This simple informative tool by Statistics Canada has the capabilities to search for Indigenous languages within Canada and within different provinces.

Should you learn an Indigenous language(s)? Duncan McCue's answer would be a resounding, "Yes," even for non-Indigenous speakers. If you are interested in learning more, where could you start? A great place to start is here. You can select which Indigenous language(s) you want to learn. Resources for Indigenous Language Learning Indigenous Language Apps: It includes a large list of indigenous language apps for your phone. Nearly all the apps are free. The list has been created by Animikii Indigenous Technology and is continuously updated. Cayuga Language Workbook by the Ontario Native Literacy Coalition Cultural Responsiveness, Competency and the Inuit Language: An induction program for educational professionals. Indigenous Language Learning: A collection of resources on the Canadian Government website. |

|

The Restory of Canadian History

This timeline is an on-going project. To add or modify events, please contact.

|

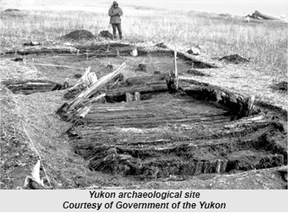

40 000 BCE

First Arrivals Waves of people began arriving around 40 000 and 11 000 years ago. They may have crossed the Bering Strait on foot as well as traveled on rafts and boats across the Pacific Ocean. |

|

15 000 BCE

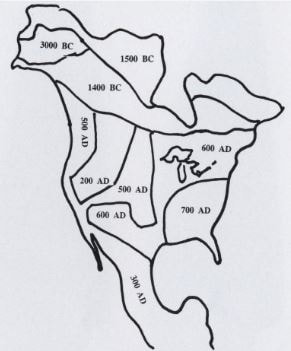

Bow and Arrow Probably the Inuit introduced the bow and arrow to North America around 3000 BC. Prior to the invention of the rifle, it was a common weapon. Bow and arrow artifacts have been found at sites in Alaska and northern Canada with dates around 1500 BC. This weapon moved southward around 600-700 CE, Southeast in 700 CE and the Western United States by 500-200 CE. |

|

1763

Royal Proclamation It set guidelines in North America for European settlement on Indigenous lands. The Royal Proclamation was issued by King George III. It recognizes First Nations consent as a requirement in negotiating for their land. From the 1750's and onward, a number of treaties were signed between the Crown and First Nations. Many of these treaties involved the claiming of land by the Crown in exchange for payment and/or other benefits. The Crown did not always honour their obligations, resulting in land disputes in Canada. |

|

1842

The Bagot Commission Report The report proposed federally-run, religious, agricultural-based Indian Residential Schools, separating children from their parents. It also mandated having only one legal status for Indigenous people, including the Métis. The goals of these actions were to force assimilation and erase indigenous identity by imposing British citizenship. |

|

1857

The Gradual Civilization Act It promoted voluntary enfranchisement, a legal process terminating Indian status to gain full British citizenship. Only debt- free males over 21 who could read and write were eligible for full citizenship. This included the right to vote and 50 acres of land. Approval was decided by a non-Indigenous board. |

|

1867

Canadian Confederation This was the coming together of the British North America Act (BNA). Many groups including Indigenous groups were not included in these processes. Three colonies were made into 4 provinces (Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick). In Section 91, the federal government is charged with responsibility for "Indians and lands reserved for Indians." This created a provincial system for health and education and a separate system for Indigenous people. |

|

1884

Potlatch Ban The federal government made these traditional gift-giving feasts practiced by the Northwest Pacific Indigenous people illegal. They considered them anti-christian and wasteful. According to U'mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, potlatch refers to the ceremony where families gather to give names, announce births, conduct marriages and where families mourn loved ones. It also includes a ceremony where a chief passes on his rights and privileges to his eldest son. Witnesses are given gifts. |

|

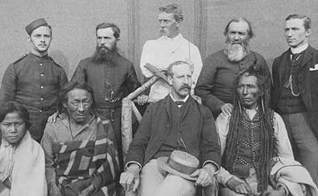

1885

The Northwest Rebellion The uprising by the Métis people of Saskatchewan under Louis Riel was not successful. Included in the photograph are, beginning in the back row, from left to right: Constable Black, Louis Cochin, Inspector R.B. Deane, Alexis Andre, and Beverly Robertson, and in the front row, Horse Child, Chief Big Bear, Alexander Stewart, and Chief Poundmaker. |

|

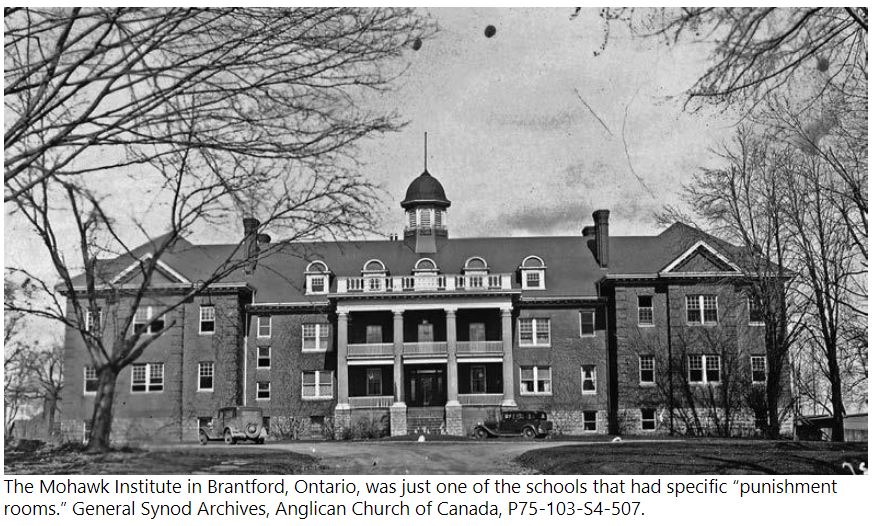

1892

Agreement between the Canadian Government and Christian Churches The Roman Catholic Church, the Church of England (Anglican), the Methodist (United) Church, and the Presbyterian Church were to run the schools for Indigenous children. Indigenous children were not allowed to attend public schools until 1945. Parents had to sign over custody to the superintendent or principal of these schools. Children were also forcibly taken. Mass graves have been found around and within walls and foundations. |

|

1939

The Second World War 1939-1945 Over 3000 Indigenous people served including over 70 Indigenous women. The picture is of Thomas George Prince and his brother Morris Prince. Thomas left Brokenhead First Nations in Scanterbury, Manitoba to work for the Royal Canadian Engineers. Later, he worked in the Canadian Special Service Battalion, which became the 1st Special Service Force. |

|

1951

Funding Initiatives in Public Schools Canada entered into financial agreements with provinces and territories. Provincial schools received funding based on how many children attended from reserves. This funding initiative required little to no accountability to ensure funds were used to help provide quality education for Indigenous students. |

|

1969

Claims Commission and a White Paper for Assimilation An Indian Claims Commission was created by the Canadian government to deal with land claims. That same year, the federal government’s White Paper called for the assimilation of First Nations people into Canadian society. |

|

1972

Indian Control of Indian Education Policy This was drafted by Harold Cardinal in 1970 as a response to the White Paper of 1969. It was submitted to the federal government and informally called the Red Paper in 1972. In 1973, a policy was created and implemented called "Indian Control of Indian Education." It aimed to revitalize Indian education, cultures and economies instead of assimilation and lost of identities. This did not change Canada's fiduciary responsibility for First Nation education, but enable Indigenous people to enhance others and their own educational capacity. |

|

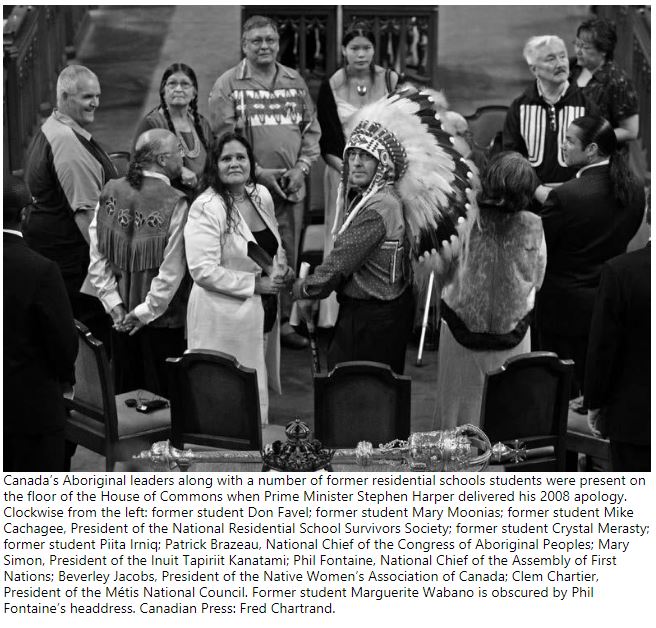

2008

Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission It was launched by the Government of Canada. Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a formal apology for the treatment of Indigenous people in residential schools. The commission concluded that residential schools constituted an assault on indigenous children, families, culture, self-governing and self-sustaining indigenous nations, and the negative effects were immediate and on-going. There was mixed thoughts about the process and the result. |

|

2011

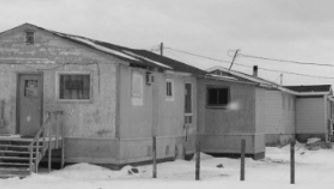

Attawapiskat Crisis In this Northern Ontario community there was a winter housing crisis. It sparked discussion about the living conditions of Indigenous people, especially First Nations. The crisis continued as suicide epidemic was declared a state of emergency in 2016. |

|

2012

Summit Meeting focusing on the Needs of First Nations The meeting included 100 First Nations chiefs was held by Harper. The main focus was the needs of First Nations including funding. |

|

2016

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls It was created under Justin Trudeau. By 2018, more than 697 families and survivors have shared stories of violence, including murder, against Indigenous females. The mandate also includes examining practices and policies to eliminate systematic causes. |

|

2018

National Indigenous Languages Revitalization Act The act has been in co-development with the federal, provincial and territorial ministers of culture and heritage and the Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and the Métis Nation for three years. It is nearing the finalization processes and aims to revitalize and protect 58 Indigenous languages. |

Additional Timeline Resources

A Timeline of Alberta's Indigenous History Stepping Stones is a publication of the Alberta Teachers’ Association Walking Together Project intended to support certificated teachers on their learning journey to meet the First Nations, Métis and Inuit Foundational Knowledge competency in the Teaching Quality Standard. Walking Together would like to acknowledge the contributions of Alberta’s First Nations, Métis and Inuit community members in developing these resources.

A Timeline for Aboriginal Justice and Determination The source of the material is from Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

A Learning Journey: Thoughts, Questions and Wonderment

|

February 8, 2018

I watched the video with Linda Tuhiwai Smith and Eve Tuck. I learned a lot about things that I knew very little about, particularly Indigenous Methodology and Indigenous knowledge. I hope as I read Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit, I gain an even better understanding about Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing.

Smith outlines the historical account of the Maori and how they were denied their history and way of life. It saddens me to think about this history. What if my family and I were denied the right to speak our language, tell our stories and practice our beliefs and customs? I imagine fear would be replaced with anger and eventually numbness. The Maori's knowledge was considered irrelevant and many perceived it as harmful and wrong. |

Decolonizing Methodologies: Linda Tuhiwai Smith and Eve Tuck

|

The actions of non-Indigenous people, also negatively influenced many Maori's perceptions of knowledge production and science. This resulted in many Maori not participating in science and knowledge production. Smith discusses how non-Indigenous people would come to their homes to collect blood samples from them- traumatic and tragic. Another factor which negatively influenced scientific participation was personally felt by Smith. She explains how Eurocentric research methods did not relate to how she understood knowledge production as an Indigenous person. She rightly accuses many academic institutions of misusing their power as learning and research institutions because they are implicated in colonialism and orientalism. Had I experienced something similar? Did what I learned in elementary, secondary, bachelor and master programs reflect who I was? What version of the truth had I been taught...and why?

Smith doesn’t accuse to accuse. She wants to see changes to research methodology and how knowledge is created, produced, understood and reproduced. This process of restoring Indigenous knowledge must address layers of imperialism by both Indigenous and non-indigenous people. She makes an important distinction that Indigenous communities must use their ways of knowing, recovery, resistance, creativity, development, survival and healing to effectively restore Indigenous knowledge. This would lead to an inclusion of Indigenous knowledge but also a process of examining, questioning and taking actions to systematically address Eurocentrism.

She provides many solutions to bring about changes. Eurocentric ways of knowing will not work within Indigenous communities. Chrisjohn, Young and Maraun (2003) support this when they describe the failure of the 2008 Truth and Reconciliation actions. Indigenous people must revitalize their languages, bring together families (elders, parents and kids) for inter-generational development, re-generate culture and find a way of being to practice hospitality and reconcile within society. It will not be an easy task. As Smith points out, Indigenous people are faced with many Eurocentric systems and attitudes which view Indigenous knowledge as less. This is not the case. She uses the example of First Nations people not accidentally finding land, but purposefully voyaging to new places to demonstrate how Indigenous knowledge is both relevant and powerful.

As Tuck points out many people can benefit from Indigenous methodology and knowledge. These Indigenous ways of knowing can contribute to sustainability, ethical and spiritual relationships, language and security and wider research agendas. Personally, I want to know more, but also I need to be cautious as I maneuver through information that is quite new to me. For instance, as I was writing this, I first made the word “Indigenous” lowercase, but “Eurocentric,” uppercase, unconsciously. I went back and changed it.

I am interested in understanding more about Indigenous methodologies and wonder if I will understand it well, being a non-Indigenous person. I assume my lack of understanding of Indigenous languages will be a significant obstacle. However, I will push forward. I also hope to have a better understanding of the history that occurred here on Aboriginal lands. As I continue, reading books and viewing media related to Indigenous people, I hope to understand the world as it was and the world that it is as well as the world it could be.

The actions of non-Indigenous people, also negatively influenced many Maori's perceptions of knowledge production and science. This resulted in many Maori not participating in science and knowledge production. Smith discusses how non-Indigenous people would come to their homes to collect blood samples from them- traumatic and tragic. Another factor which negatively influenced scientific participation was personally felt by Smith. She explains how Eurocentric research methods did not relate to how she understood knowledge production as an Indigenous person. She rightly accuses many academic institutions of misusing their power as learning and research institutions because they are implicated in colonialism and orientalism. Had I experienced something similar? Did what I learned in elementary, secondary, bachelor and master programs reflect who I was? What version of the truth had I been taught...and why?

Smith doesn’t accuse to accuse. She wants to see changes to research methodology and how knowledge is created, produced, understood and reproduced. This process of restoring Indigenous knowledge must address layers of imperialism by both Indigenous and non-indigenous people. She makes an important distinction that Indigenous communities must use their ways of knowing, recovery, resistance, creativity, development, survival and healing to effectively restore Indigenous knowledge. This would lead to an inclusion of Indigenous knowledge but also a process of examining, questioning and taking actions to systematically address Eurocentrism.

She provides many solutions to bring about changes. Eurocentric ways of knowing will not work within Indigenous communities. Chrisjohn, Young and Maraun (2003) support this when they describe the failure of the 2008 Truth and Reconciliation actions. Indigenous people must revitalize their languages, bring together families (elders, parents and kids) for inter-generational development, re-generate culture and find a way of being to practice hospitality and reconcile within society. It will not be an easy task. As Smith points out, Indigenous people are faced with many Eurocentric systems and attitudes which view Indigenous knowledge as less. This is not the case. She uses the example of First Nations people not accidentally finding land, but purposefully voyaging to new places to demonstrate how Indigenous knowledge is both relevant and powerful.

As Tuck points out many people can benefit from Indigenous methodology and knowledge. These Indigenous ways of knowing can contribute to sustainability, ethical and spiritual relationships, language and security and wider research agendas. Personally, I want to know more, but also I need to be cautious as I maneuver through information that is quite new to me. For instance, as I was writing this, I first made the word “Indigenous” lowercase, but “Eurocentric,” uppercase, unconsciously. I went back and changed it.

I am interested in understanding more about Indigenous methodologies and wonder if I will understand it well, being a non-Indigenous person. I assume my lack of understanding of Indigenous languages will be a significant obstacle. However, I will push forward. I also hope to have a better understanding of the history that occurred here on Aboriginal lands. As I continue, reading books and viewing media related to Indigenous people, I hope to understand the world as it was and the world that it is as well as the world it could be.

February 15, 2018

Prior to reading Battiste’s book, I saw there was an article she wrote about Indigenous knowledge. Battiste (2002) provides in-depth information on Indigenous knowledge and describes it as a holistic paradigm and a cognitive system which includes Indigenous language, worldviews, teachings and experiences. She also describes it as filling in ethical and knowledge gaps in Eurocentric education and research. Other benefits that were mentioned include sharing capacities, lowering poverty and creating sustainable development.

To balance colonial and neocolonial practices, Indigenous people need to define their own capacity for epistemology and validity. It is important to note, especially since I had problems at first identifying my own biases in this statement: “Indigenous knowledge is now seen as an educational remedy that will empower Aboriginal students if applications of their Indigenous knowledge, heritage and languages are integrated in the Canadian Education System.” I related this directly to cultural responsive teaching and did not finding it problematic. However, after thinking about it, I agree that indigenous knowledge is not about fixing a “problem,” but a way of knowing.

Indigenous ways of knowing is largely missing from the Canadian Education System. How we are connected and especially our spiritual identities are not addressed in the school system. How can we expect students to learn without their “whole-selves?” I believe sharing diverse identities builds bridges between people and provides individuals with opportunities to accept, adapt and even adopt diverse perspectives.

For Indigenous knowledge to be prevalent in society, young people, especially, must feel Indigenous knowledge is rewarding to pursue within their lives and careers. How prevalent Indigenous knowledge is will affect the fabric of society by including a holistic paradigm into Canadian life.

Why is there so much resistance? I know- but it shouldn't be this difficult to embrace diverse perspectives. Why would you want to limit your ideas and experiences if it could possibly lead to a better life with an increased ability to reflect, collaborate and solve meaningful issues?

To balance colonial and neocolonial practices, Indigenous people need to define their own capacity for epistemology and validity. It is important to note, especially since I had problems at first identifying my own biases in this statement: “Indigenous knowledge is now seen as an educational remedy that will empower Aboriginal students if applications of their Indigenous knowledge, heritage and languages are integrated in the Canadian Education System.” I related this directly to cultural responsive teaching and did not finding it problematic. However, after thinking about it, I agree that indigenous knowledge is not about fixing a “problem,” but a way of knowing.

Indigenous ways of knowing is largely missing from the Canadian Education System. How we are connected and especially our spiritual identities are not addressed in the school system. How can we expect students to learn without their “whole-selves?” I believe sharing diverse identities builds bridges between people and provides individuals with opportunities to accept, adapt and even adopt diverse perspectives.

For Indigenous knowledge to be prevalent in society, young people, especially, must feel Indigenous knowledge is rewarding to pursue within their lives and careers. How prevalent Indigenous knowledge is will affect the fabric of society by including a holistic paradigm into Canadian life.

Why is there so much resistance? I know- but it shouldn't be this difficult to embrace diverse perspectives. Why would you want to limit your ideas and experiences if it could possibly lead to a better life with an increased ability to reflect, collaborate and solve meaningful issues?

|

February 22, 2018

I have heard the term “orientalism” referred to, but did not have a good grasp on how it related to knowledge production. I found it hard to accept classifying and putting things into parts as a Eurocentric way of thinking.

The video helped me understand how my own education has influenced how I view others. I remember some of the textbook images of different cultural groups and the information that I was taught in school. During that time, I don't remember wondering or asking if this portrayal of different people and cultures were accurate. |

|

Our assumptions of people and places can be dangerous things. It can place people and groups in positions of superiority and inferiority as well as perpetuate inaccurate information. And yet, we have these assumptions- produced by direct and indirect experiences. Do we just deny these thoughts and pretend they do not exist? Or should we face them? I think we should confront ourselves and the information around us. We must reflect on our ideas and be critical consumers of knowledge. Where did this information come from (what sources)? Who is benefiting from this knowledge? Who is not?

The truth is people make assumptions and form stereotypes. If someone asked me to visualize a place I had never gone to, I probably would already have certain assumptions about the place and the people based on images I have seen or a conversation I have listened to. On a larger scale, these kind of thoughts, especially when acted upon, can have detrimental effects on people. These thoughts can start wars, cause death and inter-generational trauma, which many Indigenous people in Canada are facing. Isn't it time we looked inward for outward change?

When I set out to see the world 12 years ago, I remember a situation which changed my perception about myself, the world and stereotypes. At the time, I considered myself to be an open, free-spirited person who was excited to embrace new experiences, cultures and so forth. While in Spain, I met a group of people from Afghanistan. An image invaded my thoughts. I immediately imaged individuals carrying large, automatic weapons. Perhaps, mostly unconsciously, I proceeded cautiously as I introduced myself. My understanding of Afghani people was based on what I had read in the newspaper- terrorist attacks. Obviously, the image I had in my head was absurd. It doesn't make common sense to equate all Afghani people with terrorism and violence. As you might of guessed, the people I met were warm, wonderful people, not violent. They didn't own weapons of any kind. Unless you consider kitchen utensils dangerous. I've known these people for years now and even learned some Pashto, but I won't ever forget how wrong my initial reaction to them was. This was an important learning moment for me, and a reminder that biases are experienced by everyone. We must challenge our own thoughts or we may become victims of them.

The truth is people make assumptions and form stereotypes. If someone asked me to visualize a place I had never gone to, I probably would already have certain assumptions about the place and the people based on images I have seen or a conversation I have listened to. On a larger scale, these kind of thoughts, especially when acted upon, can have detrimental effects on people. These thoughts can start wars, cause death and inter-generational trauma, which many Indigenous people in Canada are facing. Isn't it time we looked inward for outward change?

When I set out to see the world 12 years ago, I remember a situation which changed my perception about myself, the world and stereotypes. At the time, I considered myself to be an open, free-spirited person who was excited to embrace new experiences, cultures and so forth. While in Spain, I met a group of people from Afghanistan. An image invaded my thoughts. I immediately imaged individuals carrying large, automatic weapons. Perhaps, mostly unconsciously, I proceeded cautiously as I introduced myself. My understanding of Afghani people was based on what I had read in the newspaper- terrorist attacks. Obviously, the image I had in my head was absurd. It doesn't make common sense to equate all Afghani people with terrorism and violence. As you might of guessed, the people I met were warm, wonderful people, not violent. They didn't own weapons of any kind. Unless you consider kitchen utensils dangerous. I've known these people for years now and even learned some Pashto, but I won't ever forget how wrong my initial reaction to them was. This was an important learning moment for me, and a reminder that biases are experienced by everyone. We must challenge our own thoughts or we may become victims of them.

March 8, 2018

To be honest, reflecting doesn't come natural to me. I kind of feel uncomfortable with thinking about myself. It might stem from feeling exposed or wondering if anyone is actually interested in what I am discussing. One thing I noticed while reading Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit (Battiste, 2013) was at times I felt like the "other." I felt left out of the inner circle as someone who is non-Indigenous reading about Indigenous empowerment. I thought about how the children in residential schools must of felt being taught about worldviews they didn't relate to and in a language that wasn't their choice to learn. How it must of felt to be told not to speak your first language and told your ways are irrelevant to modern society. What I felt reading some parts of the book, obviously, pale in comparison of the trauma residential school survivors face/faced.

One thing I noticed about feeling like the "other" is, I wondered where I "fit in" within decolonizing education. Was there room for me? In the book, the forward is written by Rita Bouvier, and she opens with "Tawow! Tawow! Tawow! (p.8)." This translates into "there is room here [for everyone]." I found myself thinking of this as I read through the book. It gave me hope that I wasn't just a spectator but a participant. I have a place within the framework of decolonization. And I did.

I didn't feel disconnected through the whole book, especially as ideas were shared about possible actions I could take.

One thing I noticed about feeling like the "other" is, I wondered where I "fit in" within decolonizing education. Was there room for me? In the book, the forward is written by Rita Bouvier, and she opens with "Tawow! Tawow! Tawow! (p.8)." This translates into "there is room here [for everyone]." I found myself thinking of this as I read through the book. It gave me hope that I wasn't just a spectator but a participant. I have a place within the framework of decolonization. And I did.

I didn't feel disconnected through the whole book, especially as ideas were shared about possible actions I could take.

REFERENCES

Battiste, M. (2002). Indigenous knowledge and pedagogy in First Nations Education: A literature review with recommendations. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Ottawa

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon, SK: Purich Publishing.

Chrisjohn, R.D., Young, S.L., & Maraun, M. (2003). The Circle Game: Shadows and substance in the Indian residential school experience in Canada. Penticton, BC: Theytus Books Ltd.

|

Diversity is Our Reality. Inclusion is Our Choice.

Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada © Copyright 2017 Inclusion Canada All rights reserved

Created, Designed, Developed and Written by Lisa Goolcharan |