|

“First: all humans are sacred, whatever their culture, race, or religion, whatever their capacities or incapacities, and whatever their weaknesses or strengths might be” (p. 14).

Jean Vanier, Becoming Human (2008) |

Developing Inclusive Education &

Addressing Social Justice

|

Effectively addressing diversity in schools and communities is an ongoing, universal challenge (Riehl, 2000) necessary for the success of all. Inclusive education necessarily involves diversity education. Diversity education is greatly needed in “a world dominated by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity” (Shields, 2013) and as Anderson (2004) highlights, effective instruction includes inclusive educators who learn to see classroom events through the many lenses of their students. Canada is no exception. Our diverse nation influences and is influenced by local, national and international volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. Despite being a multicultural nation, “Canada and indeed Canadian law and public policy more generally, has often been more about diminishing, covering up, or managing difference than about learning to engage constructively in wrestling with the very real issues [diversity education] raises (Peck et al., 2010; Bickmore, 2014; Buckingham, 2014 as cited by Hamm, Peck and Sears, 2018, p. 102). The intergenerational decline of Indigenous languages and ways of knowing as well as the ongoing achievement gaps between marginalized and non-marginalized individuals reflect a nation that has not collectively embraced diverse identities, perspectives and ways of knowing.

Care and concern about inequities is not enough without purposeful, thoughtful actions from all cohorts. With diversity, inclusion and social justice in the forefront of educational reform, all students benefit from greater opportunities for diversified learning and leadership. These learnings increase critical consciousness, global citizenship within the new world economy, and develop personal and collective well being, acting for the common good. The imminent need for inclusive leaders, especially those in education, to recognize, appreciate and promote the importance of diversity and equitable practices in schools and communities provides opportunities for individual and global growth, prosperity and social justice (Moore, 2016; Ryan; 2006; Shields, 2013). As a result, the aim is for all learners and leaders, not just school administration, to contribute to educational research and embrace inclusive practices. There are many complicating issues around diversity and inclusive education. Careful consideration of both the rhetoric and the reality of this change as well as its processes are critical as democratic societies, including those in Canada, become increasingly diverse. Collectively exploring and examining multiple definitions and understandings of inclusion, complex processes of overturning systematic exclusionary practices and developing inclusive practices build a common framework for inclusive transformations. These transformations must support diversity and inclusion awareness, leadership and instructional support and establish a collaborative social justice platform to explore, plan, implement and revisit inclusive actions. Transformational, transformative and inclusive leadership models provide the foundation for an integrated model which empowers all stakeholders in building a positive culture to directly address social justice issues. Additionally, in the classroom, educators must utilize the strengths of all learners and integrate pedagogical approaches to support critical dialogue, culturally and linguistically responsive education, and authentic learning experiences to better connect schools to home life and the community (Riehl, 2000; Theoharis & O’Tool, 2011). Integrated leadership models combined with key professional learning and instructional elements such as critical pedagogy and language enhancement/development of biliteracy and multilingualism provide educational teams with opportunities to counteract inequalities and reap the benefits of diversity and inclusion. The Rhetoric of Inclusion Further complicating issues around inclusive education and diversity is the rhetoric which includes multiple definitions and understandings of inclusion. Nilhom and Göransson (2017) find different types of articles define and understand inclusion differently and uncover four concepts of inclusion: the placement of students; the provision of specific students with special needs and the provision of all students as well as the creation of communities. They urge researchers to agree upon one definition for the advancement of inclusive education but provide no insight into which definition should be used. Alternatively, multiple definitions of inclusion can enrich the study of inclusive education by providing the means for researchers to explore a wider range of foci, approaches and perspectives. Opertti, Walker and Zhang (2014) show how multiple definitions of inclusion benefit researchers by illustrating the continually evolving journey of inclusion starting with the human rights perspective in 1948 and a response to children with special needs in 1990. These contributions to inclusion research were followed by other contributions such as a response to marginalized groups in 2000 and transforming education systems in 2005. Another significant study by Ainscow, Booth and Dyson (2006 as cited in Messiou, 2017) embraces six ways of thinking about inclusion including a principled approach used on this site. Inclusion as a principled approach to education and society includes “inclusive values, such as equity, participation, community and respect for diversity, is seen as important in guiding overall policies and practices” (p.147). The Reality of Exclusion and Diversity Awareness Another challenge in developing socially-just, inclusive schools is overturning exclusionary practices that prevent access to education for all learners. Méndez-Morse (2013) illustrates “how woefully unprepared many school and district leaders are to adequately lead, create, and cultivate educational environments where all the children in their care are achieving academic success” (p. 105). Social justice requires schools to shift focus from the majority to include minorities (Moore, 2016). Exclusionary practices are not random but systematic even though diversity, such as religious beliefs, cultural values and sexual orientation are predominantly hidden. (Banks, 2004; Gay, 2013; Shields, 2013). Achievement gaps are the result of systematic inequalities such as inadequate inclusion of diverse groups (ethnicity, language, gender, socio-economic status, ability and sexual orientation) and acknowledgement and acceptance of complex intersectional identities (Grant & Zweir, 2011) in a shared vision for diversity-rich practices, processes and strategies within schools and communities (Shields, 2013). Inclusive Framework

|

|

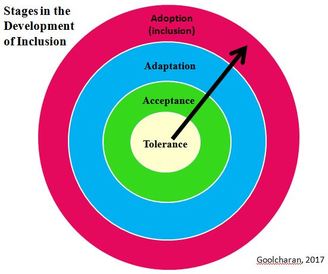

Individuals and teams who embrace diversity and inclusion, promote enormous benefits for themselves and society, as a whole. Diversity and inclusive education requires leaders to recognize both positive and negative responses to diversity, and plan deliberate thoughtful professional learning that supports effective inclusion. Cycles of focused inquiry about diversity, inclusion and social justice should consider both the integration of inclusive leadership and professional learning models and enhance inclusive practices in classrooms, schools and communities. To this end, the reflective practices of individual leaders and collective leadership teams support moving beyond tolerance to accepting, adapting and adopting diverse perspectives to solve an array of complex problems with greater natural, human and economic resources.

The process of developing professional learning teams is both a process and product. In the early stages of professional learning team development clarify their understanding of educational reform and develop guidelines of engagement in cycles of inquiry about their identities, contexts and sharing diversity and inclusion research. A common misunderstanding of educational reform is assuming the entire education system must change. This all-or-nothing attitude often results in stakeholders feeling overwhelmed and under-prepared for a multitude of changes. These kinds of environments decrease the likelihood of both short and long-term successes. However, educational reform, including changes for inclusion and social justice are more impactful with a focus on critical changes to support all students’ academic, social, emotional and physical well being. To support all students, collaborative teams should consider engaging in short focused cycles of inquiry and learning around diversity, inclusion, leadership and social justice. According to Breakspear (2017), short focused cycles of inquiry and learning can clarify, incubate and amplify localized and organizational collaborative decision-making processes for sustainable behavioral and attitudinal shifts. He highlights how these short learning cycles help individuals cope with complex educational reform to inform the allocation of environmental, human and economic resources. Beyond facilitating inclusive practices, successful collaborative learning teams who embody inclusive values, examine, discuss and prioritize the development of inclusive internal and external processes and professional learning. This requires individuals and teams to mindfully reflect on themselves and others and actively adapt and adopt diverse perspectives to local context (Goolcharan, 2017). Cycles of inclusive professional inquiry and learning are inclusive of student, teacher and community identities, contexts and emotions by inviting, understanding, and empowering diverse perspectives. Throughout this process, learning teams re-visit, re-imagine and re-mobilize professional learning and leadership development, support diversity and inclusion awareness, and encourage inclusive instructional methods and strategies. These factors significantly contribute to the diverse lives of students, families and local, national and international education systems. Leadership takes many forms and influences how people view themselves, the world and ultimately affects local and global progress. To build greater capacity, collaborative teams can explore the use of an integrated leadership model. Before leaders enact an integrated leadership model, reflective practices aid in planning strategically. Leaders can explore their personal and professional identities, their context and the people in them as well as the growing demands of a more connected world. Leaders who prepare strategically for active student, teacher, administration, parent and community member engagement are more likely to provide opportunities for the education of every student. For inclusion to occur meaningfully, intentionally including stakeholders in inclusive processes and products as well as consistently helping stakeholders develop relationships and build capacity about social justice must be considered higher priorities. As leaders engage in collective inclusive processes modelling inclusion, active learning, critical dialogue, a growth mindset and providing opportunities for personal, professional and community development aid in collective understanding and success. Several leadership models are useful in promoting inclusive practices and transforming education. Integrating transformational, transformative and inclusive leadership are the three most effective models in promoting inclusion. These leadership models help develop school culture, address inequalities and actively involve all stakeholders in collaborative processes. Transformational leadership improves school culture and creates a collaborative school vision, builds relationships and promotes community involvement. Transformational Leadership in education was first developed by Bass (1984) and Leithwood (1994). If focuses on building shared commitments and organizational capacities (Leithwood & Duke, 1998). Bi and Ehrich (2012) characterized transformational leaders by their “risk taking, goal articulation, high expectations, emphasis on collective identity, self-assertion and vision” as well as their belief in social justice. Alternatively, transformative leadership explicitly addresses inequalities, deconstructs and reconstructs knowledge frameworks and redistributes power. James Macgregor Burns (1978), historian and scientist, was one of the first to write about leadership that transforms and results in "real change--that is, a transformation to the marked degree in the attitudes, norms, institutions, and behaviors that structure our daily lives (p. 414). “Transformative educational leadership begins by [questioning and] challenging inappropriate uses of power and privilege that create or perpetuate inequity and injustice” (Shields, 2010, p. 564). Unlike, transformational and transformative leadership, inclusive leadership unquestionably supports inclusion, social justice and democratic processes. By promoting inclusion, social justice can be achieved if people are meaningfully included in practices and processes and use inclusion as a lens to address social justice issues (Ryan, 2006). Notably, the process of inclusive leadership is more than gathering people together and having fair representation but a process and product of making significant systematic changes for equity. To effectively shift focus from the majority to include the disadvantaged and marginalized in social processes for social justice, leaders should integrate transformational, transformative and inclusive leadership models to best support inclusion. By combining these models, leaders can facilitate inclusion by developing positive organizational learning cultures (Bi & Ehrich, 2012; Leithwood & Duke, 1998) that address inequalities (Shields, 2013) to ensure systematic, equitable changes for the benefit of all. These inclusive processes and products involve stakeholders in meaningful ways to transform schools (Ryan, 2006). Transforming schools will require a positive learning culture resulting in greater capacity building, inclusive practices and opportunities for social change. However, processes must be both inclusive and transformative because they must address inequalities, so all stakeholders have the supports necessary to engage in meaningful ways. "In its more advanced or effective form, an inclusive leader aims to facilitate the transforming and transformative effect of learning in the work of making provisions for the most vulnerable in the learning community" (Rayner, 2009, p. 445). Therefore, leaders should be prepared for engaging with all stakeholders to create a positive organizational learning culture to addressing inequalities for social justice. Few educational leaders, researchers and practitioners would argue against quality of instruction in schools as integral to improving education for all students. Decades of educational effectiveness research consistently shows the classroom-level as a predictor of student outcomes (Muijs et al., 2014). With aspects of the classroom relating closely to all students’ educational successes, it is not surprising that quality of instructional research is also vast and topics are highly varied. While some aspects of instructional research are widely studied, they are not necessary the most relevant or impactful to current instructional practices. For decades, the Canadian school system has been moving away from traditionally viewing learners as empty vessels and providing decontextualized learning . There is a growing awareness of learners and competent individuals with a large array of knowledge, skills and values which should be central to their development. There has been a move away from focusing solely or mostly on academic achievement to considering the whole child's well being. This shit aligns with Canada's focus on sustainability and the integration of Indigenous perspectives. Utilizing the strengths of all students, teachers, parents and community members to address local context is critical to balancing and aiding in district and global priorities. Pedagogical approaches should foster new meanings about diversity and promote inclusive practices to support critical dialogue, culturally relevant education, linguistically responsive education, and authentic learning experiences to better connect schools to home life and the community (Riehl, 2000; Theoharis & O’Tool, 2011). |

Stages in Developing Inclusive Schools for Social Justice

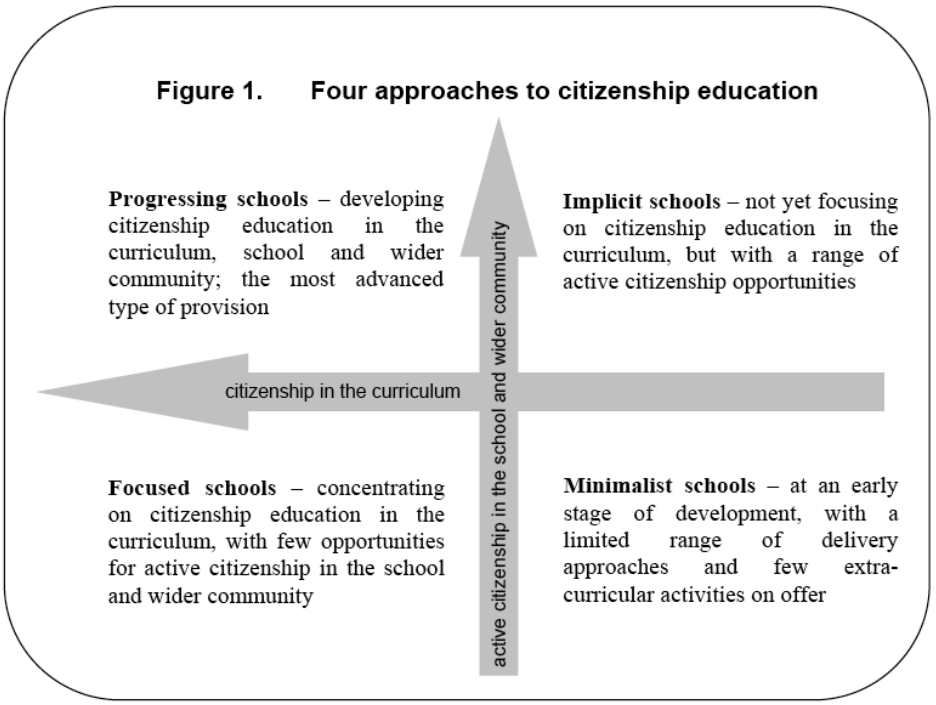

Knowing about the stages in developing inclusive schools for social justice can help schools assess where they are and plan their next steps. There was similar work in England about democratic schools. School inspectors identified four stages of movement toward democratic schools.

|

From, Cleaver, E., Ireland, E., Kerr, D., & Lopes, J. (2005). Citizenship Education Longitudinal Study: Second Cross-Sectional Survey 2004. Listening to Young People: Citizenship Education in England (No. RR626). Berkshire: National Foundation for Educational Research.

|

What Stage is your School In?

Four approaches to citizenship education (Figure 1) can relate to diversity and inclusive education by changing the variables of the two arrows: Vertical Arrow: Active inclusion in the school and wider community Horizontal Arrow: Diversity education and Inclusion in the curriculum Resulting in: Stage 1. Minimalist schools- at an early stage of development with a limited range of delivery approaches and few extra curricular activities offered. Stage 2. Implicit schools- not yet focusing on diversity and inclusion in the curriculum, but with a range of inclusive opportunities. Stage 3. Focused schools- concentrating on diversity education and inclusion in the curriculum, with few opportunities for inclusion in the school and wider community. Stage 4. Progressing schools- developing diversity education and and inclusion in the curriculum, school and wider community; the most advanced type of provision. |

What happens within each stage? How does this impact learning?

|

Stages in the Development of Inclusion

Stage 1- Tolerance. Acknowledging differences exist Stage 2- Acceptance. Accepting differences and open to understanding others. Beginning to integrate into mainstream Stage 3- Adaptation. Creating a more just society through equity. Beginning to challenge bias, take affirmative action and provide support for all learners Stage 4- Adoption. Greater collaboration and ability to relate to all individuals. Utilizing everyone's strengths for greater innovation and progress We Need to Move Beyond Tolerance As inclusion develops, each stage provides greater access to deeper learning including diverse knowledge, skills and values to solve a larger array of problems with greater impact potential. The potential for individual and collective impact increases with each stage as the mobilization of environmental, societal and economical resources increase. |

Finding Balance Between Diversity and Unity

It is not an easy undertaking to promote inclusion and social justice in schools especially with contradictory ideas being in the forefront of change. Education systems must find a delicate balance between diversity and unity as well as personal, national and global identity. Finding balance between diversity and unity is an important goal in teaching and learning especially in democratic societies (Banks et. Al. 2001). As Banks (2004) insightfully states, "unity without diversity results in cultural repression and hegemony and diversity without unity leads to balkanization and fracturing of the country" (p. 298). It is necessary for people to accept differences, adopt diverse perspectives for social justice and work collectively for sustainable change.

In addition, schools are faced with the contradictions of individualism, nationalism and globalization. Schools have a responsibility to help individuals develop their national and global identity while maintaining their own cultural identity. Banks (2004) finds cultural, national and global identity are developmentally interrelated. Therefore, individual acceptance is necessary before individuals can begin accepting others and participating on national and global platforms. This highlights two things. First of all, it is unreasonable to expect students to accept others if they cannot accept their own cultural identity and secondly, inclusion and social justice must be central to develop individuals, nationalism and globalization.

In addition, schools are faced with the contradictions of individualism, nationalism and globalization. Schools have a responsibility to help individuals develop their national and global identity while maintaining their own cultural identity. Banks (2004) finds cultural, national and global identity are developmentally interrelated. Therefore, individual acceptance is necessary before individuals can begin accepting others and participating on national and global platforms. This highlights two things. First of all, it is unreasonable to expect students to accept others if they cannot accept their own cultural identity and secondly, inclusion and social justice must be central to develop individuals, nationalism and globalization.

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. W. (2004). Increasing teacher effectiveness, Second edition. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning.

Banks, J.A. (2001). Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching, 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Banks, J.A. (2004). Teaching for social justice, diversity, and citizenship in a global world. The Educational Forum, 69, 296-305.

Bi, L., Ehrich, J., & Enrich, L.C. (2012). Confucius as transformational leader: Lessons for ESL leadership. International Journal of Educational Management, 26, 391-402. doi: 10.1108/09513541211227791

Breakspear, S. (2017). Embracing agile leadership for learning –how leaders can create impact despite growing complexity. Australian Educational Leaders, 39, 68-71.

Gay, G. (2013). Teaching to and through cultural diversity. Curriculum Inquiry, 43, 48-70. doi: 10.1111/curi.12002

Grant, C.A. & Zwier, E. (2011). Intersectionality and student outcomes sharpening the struggle against racism, sexism, classism, ableism, heterosexism, nationalism, and linguistic, religions, and geographical discrimination in teaching and learning. Multicultural Perspectives, 13, 181-188.

Leithwood, K., & Duke, D.L. (1994). Mapping the conceptual terrain of leadership: A critical point of departure for cross-cultural studies. Peabody Journal of Education, 77, 31-50.

Méndez-Morse, S. (2013). The tradition in educational leadership: Where we have come from and where we are going. In L.C. Tilman & J.J. Scheurich (Eds.), Handbook of research on education leadership for equity and diversity (pp. 105-109). New York, NY: Routledge.

Messiou, K. (2017). Research in the field of inclusive education: Time for a rethink? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21, 146- 159. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1223184

Moore (2016). One without the other. Winnipeg, MB: Portage and Main Press.

Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art- teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25, 231-256. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2014.885451

Nilhom, C., & Göransson, K. (2017). What is it meant by inclusion? An analysis of European and North American journal articles with high impact. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32, 437-451. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1295638

Opertti, R., Walker, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Inclusive education: From targeting groups and schools to achieving quality education as the core of EFA. In L. Florian (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Special Education (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 149-169). London, SAGE. Retrieved from https://repository.nie,edu.sg/bitstream/10497/17344/4/BC-IEF-2014-149.pdf

Rayner, S. (2009). Educational diversity and learning leadership: A proposition, some principles and a model of inclusive leadership? Educational Review, 61, 433-447.

Riehl, C. (2000). The principal’s role in creating inclusive schools for diverse students: A review of normative, empirical, and critical literature on the practice of educational administration. Review of Educational Research, 70, 55-81. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.proxy.hil.unb.ca/stable/1170594

Ryan J. (2006). Inclusive leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint.

Shields, C.M. (2013). Transformative leadership in education: Equitable changes in an uncertain and complex world. New York, NY: Routledge.

Theoharis, G., & O’Toole, J. (2011). Leading inclusive ELL: Social justice leadership for English language learners. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47, 646-688.

Banks, J.A. (2001). Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching, 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Banks, J.A. (2004). Teaching for social justice, diversity, and citizenship in a global world. The Educational Forum, 69, 296-305.

Bi, L., Ehrich, J., & Enrich, L.C. (2012). Confucius as transformational leader: Lessons for ESL leadership. International Journal of Educational Management, 26, 391-402. doi: 10.1108/09513541211227791

Breakspear, S. (2017). Embracing agile leadership for learning –how leaders can create impact despite growing complexity. Australian Educational Leaders, 39, 68-71.

Gay, G. (2013). Teaching to and through cultural diversity. Curriculum Inquiry, 43, 48-70. doi: 10.1111/curi.12002

Grant, C.A. & Zwier, E. (2011). Intersectionality and student outcomes sharpening the struggle against racism, sexism, classism, ableism, heterosexism, nationalism, and linguistic, religions, and geographical discrimination in teaching and learning. Multicultural Perspectives, 13, 181-188.

Leithwood, K., & Duke, D.L. (1994). Mapping the conceptual terrain of leadership: A critical point of departure for cross-cultural studies. Peabody Journal of Education, 77, 31-50.

Méndez-Morse, S. (2013). The tradition in educational leadership: Where we have come from and where we are going. In L.C. Tilman & J.J. Scheurich (Eds.), Handbook of research on education leadership for equity and diversity (pp. 105-109). New York, NY: Routledge.

Messiou, K. (2017). Research in the field of inclusive education: Time for a rethink? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21, 146- 159. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1223184

Moore (2016). One without the other. Winnipeg, MB: Portage and Main Press.

Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art- teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25, 231-256. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2014.885451

Nilhom, C., & Göransson, K. (2017). What is it meant by inclusion? An analysis of European and North American journal articles with high impact. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32, 437-451. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1295638

Opertti, R., Walker, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Inclusive education: From targeting groups and schools to achieving quality education as the core of EFA. In L. Florian (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Special Education (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 149-169). London, SAGE. Retrieved from https://repository.nie,edu.sg/bitstream/10497/17344/4/BC-IEF-2014-149.pdf

Rayner, S. (2009). Educational diversity and learning leadership: A proposition, some principles and a model of inclusive leadership? Educational Review, 61, 433-447.

Riehl, C. (2000). The principal’s role in creating inclusive schools for diverse students: A review of normative, empirical, and critical literature on the practice of educational administration. Review of Educational Research, 70, 55-81. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.proxy.hil.unb.ca/stable/1170594

Ryan J. (2006). Inclusive leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint.

Shields, C.M. (2013). Transformative leadership in education: Equitable changes in an uncertain and complex world. New York, NY: Routledge.

Theoharis, G., & O’Toole, J. (2011). Leading inclusive ELL: Social justice leadership for English language learners. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47, 646-688.

© Copyright 2017 Inclusion Canada All rights reserved

Created, Designed, Developed and Written by L. Goolcharan

Created, Designed, Developed and Written by L. Goolcharan